Reliable, sustainable and affordable energy supply is critical to economic activity, social development and poverty reduction. But two-thirds of global greenhouse gas emissions stem from energy production and use, which puts the energy sector at the core of efforts to combat climate change. In this context, the transition to less carbon intensive fuels in transport, including liquid biofuels, is fundamental. To meet the climate targets of Paris, we will need to reduce 2050 emissions to 10 GtCO2-eq/year – just a sixth of emissions projected with current R policies and Nationally Determined Contributions.

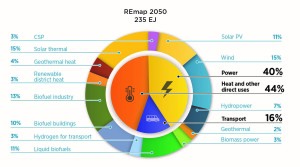

To do so, as reported to the G20, IRENA’s REmap model envisions 235 EJ of renewable energy use in 2050, with 44% for heat and other direct uses, 40% for power, and 16% for transport. In the REmap vision, roughly three-eighths of the renewable energy supply (37%) would be some form of bioenergy: 10% would be for bioenergy in buildings, 13% for bioenergy to provide industrial process heat, 11% in the form of liquid biofuels for transport, and 3% for power.

The transport market for liquid biofuels is expected to persist despite a growing trend towards electrification. As batteries provide greater energy density at lower cost, electric vehicles gain the range consumers desire and should soon cost less to buy and run than conventional vehicles. In Europe and other advanced industrial economies, most cars sold could thus well be electric by 2030, so that EVs dominate road transport by 2050. But in less developed economies where power grids are weaker, the transition will take much longer. And where biofuels based on domestic resources predominate, as in Brazil, EVs may not gain traction.

Moreover, for very heavy freight, marine shipping and especially aviation, electrification will likely remain impractical. So blending and other markets for biofuels will remain robust for decades. But how will we move to fully decarbonize the transport sector as combatting climate change requires? With increasing use of EVs alongside biofuel blending, demand for fossil fuels may be considerably curtailed. Meanwhile, shale oil supplies have been expanding faster than once anticipated. This means there could be significant downward pressure on oil prices. And if oil prices are low, how can biofuels like renewable jet fuel for aviation compete in the marketplace? This is an environmental challenge that needs to be addressed.

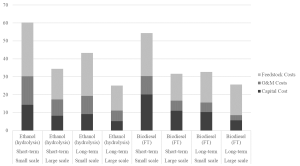

Projected costs of biofuels and fossil fuels

To better understand how big the challenge might be, it is helpful to project both biofuel and oil prices and compare them. As detailed in IRENA’s Innovation Outlook – Advanced Liquid Biofuels, technology learning and scale-up should reduce biofuel costs substantially. Total costs for advanced biofuels are shown as the sum of capital, feedstock and O&M costs in Figure 2. They are broken out for large and small plants, which differ in scale by roughly a factor of ten, for both the short-term (2015) and long-term (2045). Note that for cellulosic ethanol and biodiesel alike, long-term costs of large plants are less than half the short-term costs of small plants -showing the importance of both scale economies and technology improvement. For conventional biofuels, current costs can be taken from the literature (Iowa State University in the United States for maize ethanol and biodiesel, and Bioethanol Science and Technology National Laboratory (CTBE) in Brazil for sugarcane ethanol) and assumed to decline in the long-term by 15% to 25% due to improved production and conversion efficiency.

For the sake of comparison, the cost of fossil transport fuels (diesel and gasoline) can be estimated from crude oil price projections and their correlation with gasoline and diesel prices. Crude oil price projections can be found in the EIA Annual Energy Outlook 2017, which projects 2050 oil prices per barrel of US$117 in its reference case, $48 in a low oil price case, (with higher upstream investment by OPEC and lower OECD demand, which would be consistent with rapid penetration of electric vehicles and biofuels) and $241 in a high oil price case. The correlation between oil prices (per barrel) and spot price FOB in NY of diesel and gasoline can then be assessed through regression analysis of five years of historical data obtained from Index Mundi.

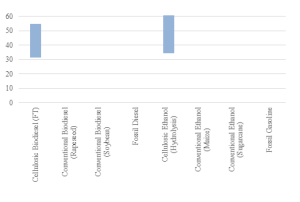

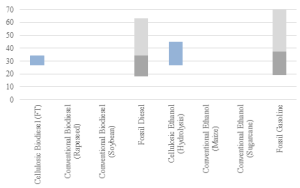

Comparative costs without a carbon value

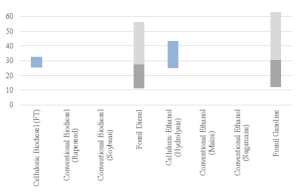

Biofuels face difficult competition from their fossil counterparts at current world oil prices, as shown in Figure 3. Even conventional biofuels, which have made significant inroads in markets like Brazil, Europe and the United States, struggle to compete with gasoline and diesel at recent world oil prices as low as $40 to $50 per barrel. Advanced biofuels face an even tougher situation, given their much higher production costs with currently available technology. The cost of advanced biofuels is shown as a range to reflect the impact of different plant scales on cost estimates. The lower bound refers to large-scale plants and the upper-bound to small-scale plants. But as oil prices have recovered to levels more like $70 per barrel in early 2018, the situation may not be so dire. In the long-term, while learning effects will bring down the costs of biofuels considerably, their competitive position will largely depend on how oil prices evolve, as shown in figure 4. If the high-oil price scenario materialised (upper bound of the fossil fuel cost bars), biofuels would compete with ease. In the reference oil price case (midvalue of the fossil cost bars where light and dark gray meet), biofuels still compete quite well, with advanced biofuels costing about the same as fossil fuels and conventional biofuels costing much less. But in the low-cost oil price scenario (lower bound of the fossil cost bars), fossil fuels would clearly remain cheaper.

Carbon advantages of sustainable biofuels

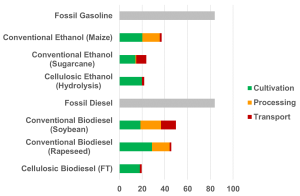

To what extent might the competitive position of biofuels be improved by a market value for carbon? Carbon emissions can be sharply reduced by shifting to liquid biofuels if they are produced from sustainable feedstocks on existing farm land or existing managed forest, as they then induce no emissions through land-use change. The typical carbon intensities of biofuels and their fossil fuel counterparts are then as shown in Figure 5, based on analysis commissioned by IRENA at PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. (Emissions will vary depending on the location, feedstock type and quality, crop yields, fertilizer use, process efficiency, transport distances, fuels used in processing and transport, and allocation of emissions between fuel and co-products.) While fossil fuels emit over 80 g CO2 /MJ, sustainably sourced conventional biofuels typically emit much less – maize ethanol less than half as much, sugarcane ethanol less than a third. And sustainable advanced biofuels – cellulosic ethanol via hydrolysis and fermentation, or cellulosic biodiesel via FT synthesis – just a quarter. The estimated feedstock emissions arise from cultivation (shown in green), processing (gold) and transport (red).

Comparative costs with carbon values internalised

The incentive provided by a price on carbon would reinforce the market position of conventional biofuels and provide a firmer competitive basis for advanced biofuels, as shown in Figure 6. Globally, IRENA estimates that the carbon price in 2050 might rise as high as $80/tCO2 . If it does, conventional biofuels (orange bars) compete well with fossil fuels even with low oil prices (bottom of light gray bars), and advanced biofuels can also compete with reference case oil prices (meeting of light and dark gray bars).

Policy support for the liquid biofuels we need

Electrification of light vehicle fleets, combined with plentiful oil supplies, may keep oil prices weak. So it may be hard for biofuels to compete with their fossil fuel counterparts in conventional economic terms. Yet biofuels are essential to decarbonizing energy use in heavy freight and marine transport and aviation. Therefore, it is important that the environmental value of reducing carbon emissions be recognised in the marketplace. And if it proves politically impossible to allow a carbon price high enough to counteract weak oil prices, it may be further necessary to require a growing share of renewable jet fuel over time, with mandated volumes. It could also make sense to limit fuel use per passenger-km and freightkm to speed improvements in aircraft fuel efficiency.

This article is by Jeffrey Skeer, Rodrigo Leme, Francisco Boshell, International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).